How to exploit a market failure

Hamish Scott-Knight looks into the great New ZealandTV opportunity. He begins with a cautionary tale.

How to exploit a market failure

Quick Summary

In 2023, New Zealand’s broadcast TV advertising revenue dropped by $74 million (14.3%), the largest decline since the global financial crisis. This decrease in ad spend far surpasses the decline in audience reach, indicating that television advertising may currently be undervalued. Astute marketers recognising this discrepancy can capitalise on television’s proven effectiveness to achieve substantial returns, similar to investors who identified undervalued assets during the GameStop surge of 2021.

How to exploit a market failure

Hamish Scott-Knight looks into the great New ZealandTV opportunity. He begins with a cautionary tale.

At some point between 2016 and 2017, US investors began to lose their collective minds.

I can best illustrate this with a single number – the share price of a company called GameStop, whose steep drop-off far outstripped a much shallower decline in revenue.

US investors, it seems, had embraced a collective wisdom – “brick-and-mortar game stores are dead.” Together with falling revenues, this was enough to induce a mass blindness towards GameStop’s other fundamentals: a vast cash reserve, steadily reducing debt, and a global physical presence that delivered ongoing foot traffic.

The market woke up to its mistake in mid-2020, when an online investment community thrust GameStop's undervalued price into the spotlight. A frenzied price correction followed. At its peak, some online investors had netted a cool $48 million from as little as $50,000 – and they did so by taking advantage of professional investors who had bet against the stock, and lost billions of their clients’ money in the process.

The moral of the story isn’t that GameStop was secretly a winner. Its business was declining, and it still is today. Instead, the story reveals our tendency to take a declining metric and act as if it were already at zero. And it reveals the gains to be made by looking at the bigger picture and uncovering the true value of an underpriced product.

Marketers are leaving money on the table

Which leads me to New Zealand in 2025. In a very different country and context, the story of GameStop is repeating. I can illustrate this simply. Look at two graphs above – see the similarity?

Somewhere between 2022 and 2023, the NZ advertising industry seems to have collectively lost sight of linear TV’s fundamentals.

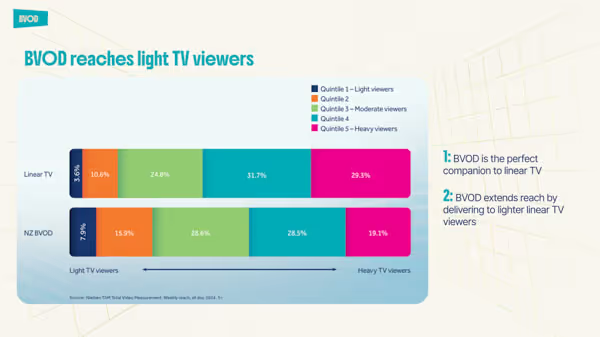

Our collective slashing of TV advertising budgets has far outpaced any change in audience (compare this to other channels, where spend and audience move together).

By itself this is a sign that something is amiss – though I’ll admit to using weekly reach, as it provided a more dramatic contrast. But audience reach is not television’s only fundamental, and there are more signs to be found.

Above reach, advertisers desire outcomes. And in recent years our industry has greatly expanded our tools for assessing whether our advertising generates these outcomes.

The overwhelming takeaway? Television’s business impact is far higher than its current price in New Zealand reflects.

Nowhere is this better highlighted than in the field of attention tracking, which has established the connection between attention and brand outcomes, while also confirming that – when weighted per dollar spent – New Zealand television generates more attention than almost any other channel.

This, alongside other advances such as the release of The Aotearoa Effectiveness Database, and the increasing production affordability offered by AI, should give New Zealand marketers more reason than ever to desire the unfair value offered by TV advertising.

But our spend is still plummeting, and today’s conversations around TV still echo those around the “death” of GameStop pre-2020.

So, here’s the thesis: by no means is TV advertising perfect for every client, or every brief. But when a market undervalues a product, there’s money on the table. Responsible investors, take note.